/create/

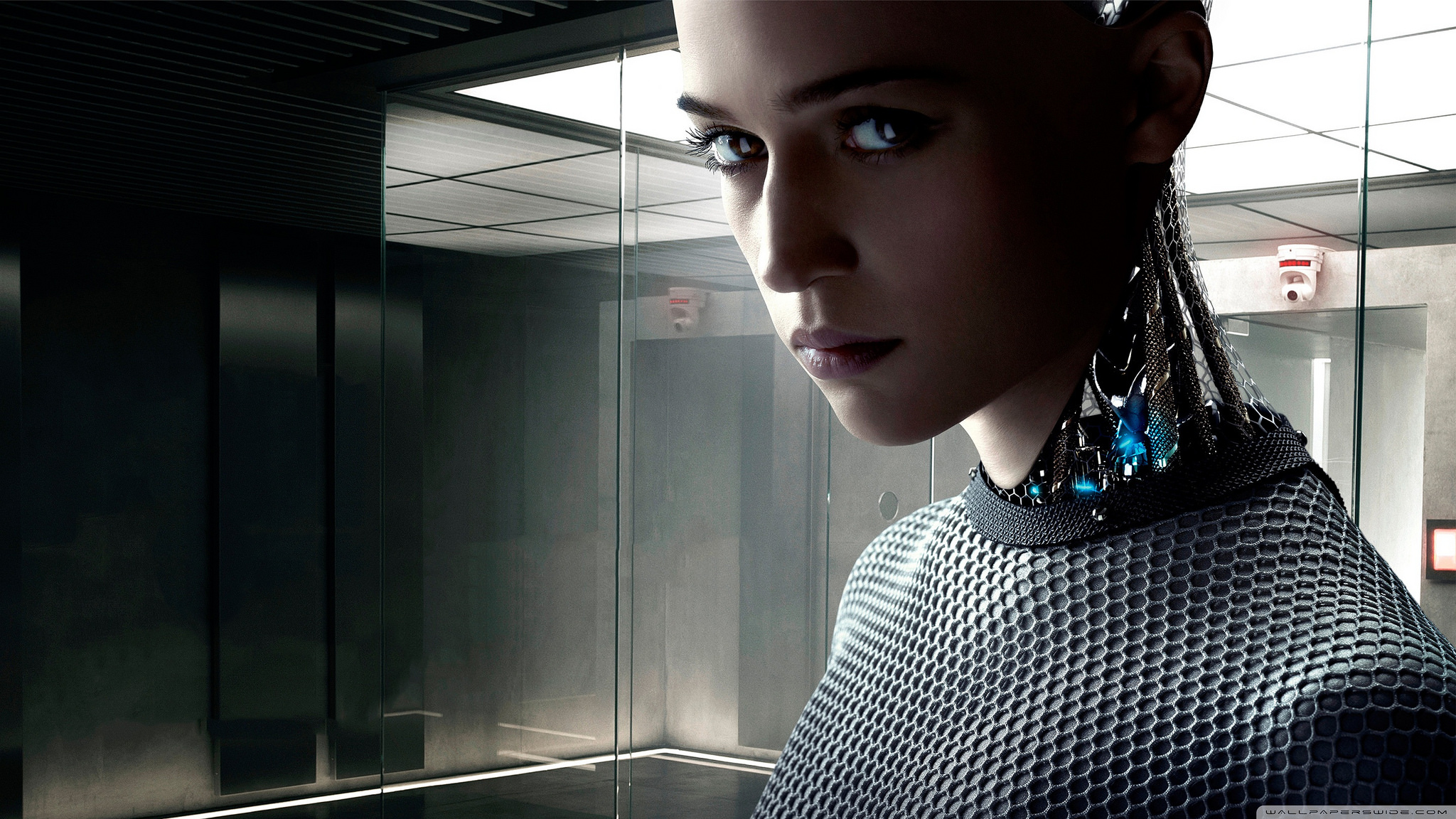

Alex Garland’s film Ex Machina may well be what the internet refers to as a problematic fave. A someone or something you admire but that has expressed certain views that are problematic. Ex Machina is a beautifully shot, compelling and well-paced directorial debut for Garland that raises some deep questions about gender, sexuality, human experience and AI, but ultimately buys into many of the snares its narrative purports to address. I want to love it and fave it and retweet because it’s beautiful and poignant it but something is lacking. While I enjoy any movie with even an ambiguous feminist message, Ex Machina points out the problem and then becomes a part of it and this recurring pattern is wearing thin. It’s depressing to imagine that even in a future where we can build a female-presenting robot that passes the Turing Test, that robot is still going to be caught up in the shit-fight of archaic gender inequality.

"It sits on both sides of the fence, cleverly pointing out how poetically tragic it is that women get the short straw while simultaneously giving women the short straw."

As has been pointed out by numerous reviewers, and hinted at by Garland, the film is a critique of gender relations and yet still buys into the same tired tropes for which sci-fi is infamous. The women in the film are young, beautiful, often naked, mostly mute and subjected. They’re kept apart and unaware of their robot sisters. The men in the film are average-looking geniuses who never take their clothes off. Garland is ambiguous about whether the film is a feminist critique, stating that sexism is in the eye of beholder, which seems like a bit of a lemon response. With all due respect Mr Garland, if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the feminist debate.

It was frustrating that a film about the morality of AI, with some potentially mind-blowing material, was reduced once again to the usual sci-fi images of two men struggling over power and sex. Until the final minutes of film our understanding of Ava, who is the most interesting character in the piece, is confined to how Caleb and Nathan know her. Caleb falls in love with Ava the ingénue, the damsel in distress and everything she says to him is a facet of that personality. Nathan built Ava, keeps her trapped and uses her as a pawn in his long game with Caleb; there’s a clear power differential between them. It’s not until the very end when Ava escapes that we see Ava as she is: a robot who DGAF. Until this point, the film is about two different versions of learned femaleness, as interpreted through the eyes of the two men. And although Caleb and Nathan are coded as the good guy and bad guy respectively, Caleb’s lofty intentions to free Ava seem to stem from his boner that he wants to put in her robotic vagina. As J.A. Michline points out, he has no beef (literally) for Kyoko and her imprisonment; not a care for the other semi-intelligent robots; no intention to stop Nathan from repeating the same experiment. He wants to free Ava specifically. Caleb is less a feminist, robot emancipator and more of a kid with a hard-on for a DID. And, as Cara Rose DeFabio notes, after Ava experiences firsthand how shitty life is when you’re female-presenting, why doesn’t she grab a prosthetic dick on the way out (I mean she has access to the ENTIRE INTERNET and she doesn’t know the world is a scary place for women? Sheesh).

There are other problematic representations in play here also. The robot women that precede Ava are of African and Asian descent. There’s also a Caucasian iteration but she is blonde, tanned and porn-star hot. These are all representations of femininity that are often marginalized, criticised and shunted to support roles. These robots were not advanced enough to manipulate the men who were trapping them and emancipate themselves. The AI iteration who is finally able to achieve freedom is delicate, Caucasian, young, full of innocence and classically beautiful. She then literally dismantles the preceding AIs and builds herself a body. What is that a comment about? It’s certainly not intersectional feminism at its best. None of it is. This is the far-reaching idea that all films, particularly sci-fi films, buy into: the sympathetic leading lady is always young, white and beautiful. We’re trained to only love her and root for her if she’s Hollywood-style perfect. In this film, her emancipation is literally built from the bodies of her fallen sisters whom she steps over to freedom. Is a film feminist if it addresses gender inequality but creates no original or diverse female characters? Or is it all talk and no trousers, jumping on the recently popularised gender bandwagon but not offering a suggestion on how to make sci-fi inclusive? Ex Machina doesn’t feel feminist.

In contrast to this is Mad Max: Fury Road (MMFR) which came out at the same time and is a feminist film in a genre typically dominated by men. The difference between the feminism addressed in the two is that one is theoretical and one is practical. Ex Machina presents food for thought on a topic which already has a vast buffet of thought; MMFR does the hard and unpopular work of making a film that features strong female characters fighting alongside men, without reducing either gender to a cardboard cut-out. I want to be Furiousa; I don’t want to be Ava or Kyoko or Caleb.

I enjoyed Ex Machina and admire it as a subtle, beautifully produced sci-fi film but labelling it as a feminist film and assessing it through the lens of what it contributes to the feminist discourse creates problems. Namely that the heroine, if she can be called that, is still played for men; she’s created by men to be beautiful and heterosexual and Caucasian, and while this may be pointing out a brutal truth about society, this representation still falls into the narrow confines of what Hollywood wants in a leading lady. It sits on both sides of the fence, cleverly pointing out how poetically tragic it is that women get the short straw while simultaneously giving women the short straw. It’s problematic that Ava wears a virginal white dress and beige kitten heels when she’s escaping through the dense woods. It’s problematic that the gratuitous nudity quotient is all carried by the women in the cast. It’s problematic that but for a few minutes of strategic murdering, this film is about a very functional patriarchy in which the female characters exist. It’s all beautifully problematic.